Original Item: One-of-a-kind set. This set is best understood by reading his in the New York Times on November 1st, 2013. Robert Rheault, Green Beret Ensnared in Vietnam Murder Case, Dies at 87

When the Army charged the Green Beret commander, Col. Robert Rheault, and six of his officers with murder and conspiracy on July 21, 1969, in the secret execution of a Vietnamese spy suspect, it caused consternation on both sides of the growing American divide over the war in Vietnam.

Hawks condemned the charges for what they saw as a Catch-22 military absurdity: the prosecution of front-line troops for killing the enemy.

Opponents of the war portrayed it as proof of American involvement in a secret campaign of terror and assassination, paralleling the combat seen nightly on television.

The seven defendants, who denied the charges, were placed in a stockade outside Saigon.

But two months later, there was a second firestorm when Stanley Resor, the secretary of the Army, said the charges against the seven defendants were being dropped because the Central Intelligence Agency — whose operatives were key witnesses — had refused to cooperate.

Colonel Rheault (pronounced row), who died on Oct. 16 at 87, spoke for his men after their release when he called the charges “a travesty of justice” and accused the Army of prosecuting “dedicated soldiers for doing their job, carrying out their mission and protecting the lives of the men entrusted to them in a wartime situation.”

The murkiness surrounding dismissal of the case, however, left Colonel Rheault and his men in a moral gray zone, neither convicted nor entirely exonerated in the murder of the man at the center of the case, Thai Khac Chuyen, a South Vietnamese translator and informant who was working with the Green Berets on covert operations in Laos.

Witnesses told Army investigators that in May 1969, Mr. Chuyen had come under suspicion of being a double agent after Colonel Rheault’s team obtained photographs showing Mr. Chuyen, or someone who looked like him, chatting with North Vietnamese Army officers.

After interrogating him for 10 days, investigators said, the Green Berets decided to execute him. He was drugged, tied, taken by boat to the middle of Nha Trang Bay and shot, the investigators said; his body, weighted with chains, was tossed over the side.

Kim Lien, his 29-year-old widow and the mother of their two children, appeared at the American Embassy in Saigon a few months later, threatening to kill herself unless she received compensation and an explanation of his death. The Army paid her about $6,000, but gave her no explanations, according to news reports at the time.

The Green Berets, an Army Special Forces group, came to prominence in the early 1960s with the support of President John F. Kennedy, who considered their counterinsurgency and unconventional warfare techniques the wave of the future in the American military.

Colonel Rheault, the son of a prominent Boston banking family, was a rising star in the Berets. Widely thought to be on the cusp of promotion to general at the time of his arrest, he had entered West Point after graduating from Phillips Exeter Academy, received a Bronze Star in Korea, earned advanced degrees in international relations and worked for the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the Pentagon before serving his first tour of duty in Vietnam as a Green Beret officer.

Promoted to commander of the Fifth Special Forces Group, overseeing all 3,500 Green Berets in Vietnam, Colonel Rheault began his command on May 30, 1969, the week the decision was made to execute Mr. Chuyen, the Army said. At the time, the C.I.A. was working with Green Berets in covert operations, and their joint efforts had been known to sow confusion in the military chain of command, an issue that figured prominently in the case.

The Chuyen execution had been approved before Colonel Rheault took over, Army investigators said. But they included him in the murder conspiracy charges, they said, because he knew of the plan and had approved his men’s cover story — that Mr. Chuyen had been sent on a mission and had not been heard from since.

Investigators never established who had given the go-ahead.

In announcing his decision to drop the charges, Secretary Resor took pains to say that execution without trial violated military code. “The Army cannot and will not condone unlawful acts of the kind alleged,” he said.

Blaming the C.I.A. for the collapse of the case, many believed at the time, indicated that he suspected the agency had somehow been involved in the killing. (Robert F. Marasco, one of the Green Berets charged in the case, told The New York Times in 1971 that he had indeed carried out the execution on the basis of “oblique yet very, very clear orders” from the C.I.A. Neither the Army nor the C.I.A. responded to that assertion.)

Colonel Rheault resigned from the Army a few months after his release. He later entered the lore of the war, though, as inspiration for two disparate Vietnam-related narratives, one fictional and one not.

John Milius, who wrote the screenplay for Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Vietnam War film, “Apocalypse Now,” told The Times in 1977 that he had based the Marlon Brando character of Walter Kurtz, the mysterious Green Beret colonel who conducts an unauthorized secret war in Cambodia, on both the fictional Kurtz of Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” and the real-life Colonel Rheault.

Colonel Rheault was “a great man,” Mr. Milius said, adding, “Men like Rheault could’ve helped us win the war.”

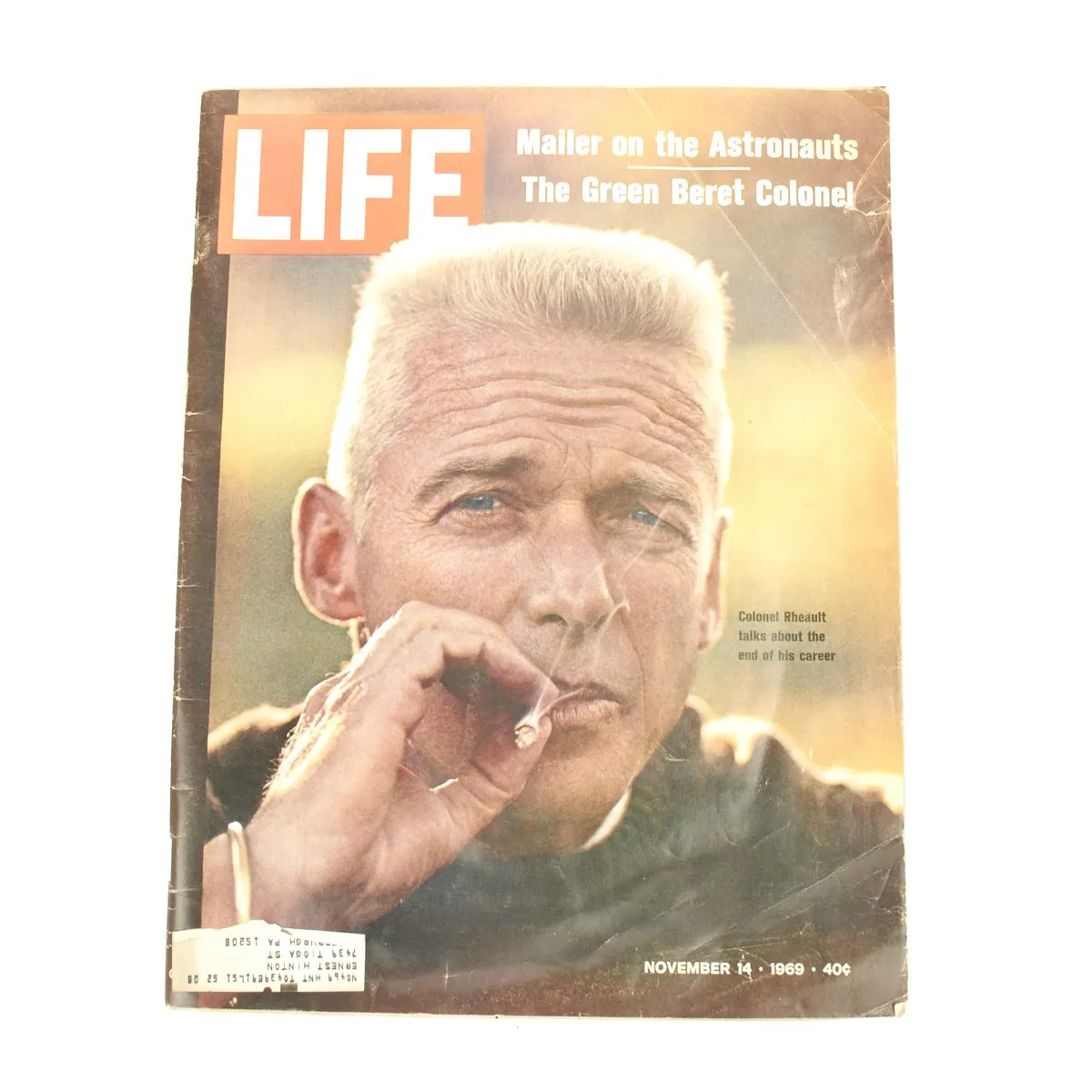

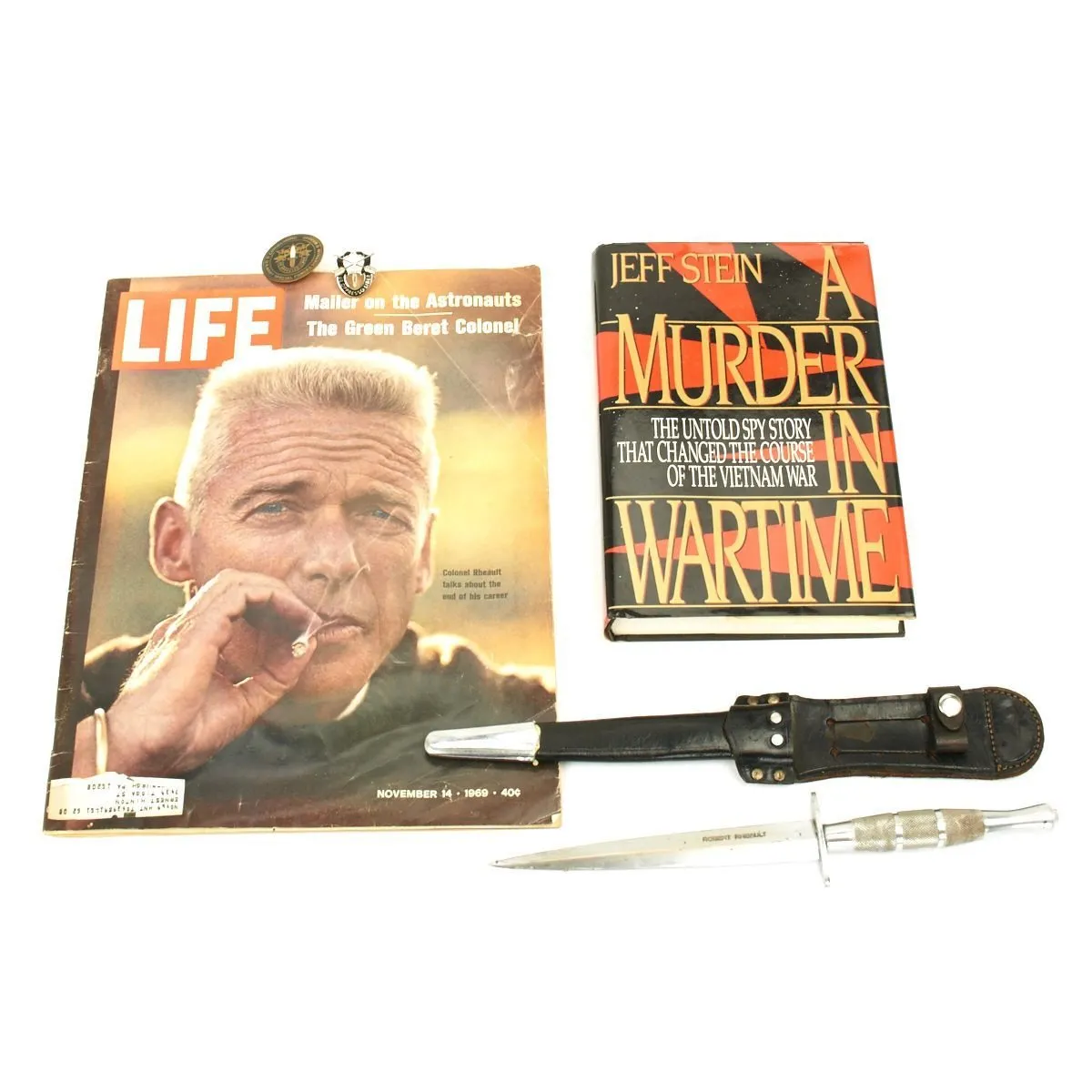

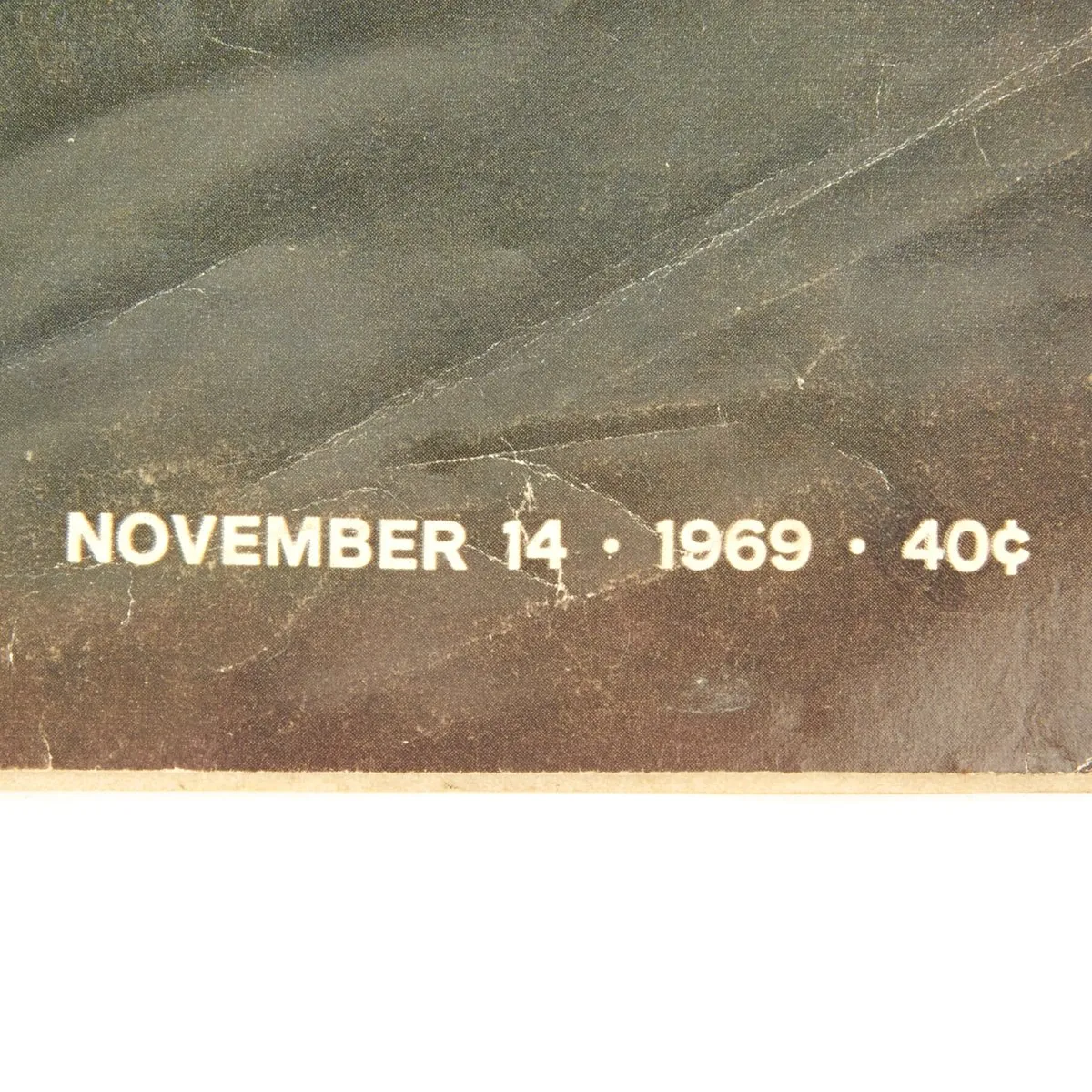

That view was expressed in an admiring profile of Colonel Rheault in Life magazine in November 1969. He was seen in a close-up photograph on the cover — inhaling a cigarette, weatherworn face coolly confronting the camera with weary G.I. resolve.

The magazine said he “exemplified national ideals of patriotism, challenge and duty.” Through no fault of his own, it said, he had been caught in the moral twilight between civilian ethics and “the aberrant, equivocal principles of war as it is waged in the shadows.”

Daniel Ellsberg saw him as a victim, too, in a sense, swallowed up by the culture of secret war. As a former Marine platoon leader in Vietnam and a high-level Pentagon analyst, Mr. Ellsberg had seen the system consume good human beings up and down the line, he wrote years later in “Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers” (2002).

Mr. Ellsberg saw the Green Beret case, as it was called, as a kind of parable about an unholy system undergirding the history of the war. “It’s a system that lies automatically, at every level, from bottom to top — from sergeant to commander in chief — to conceal murder,” he wrote. The Green Beret case, he said, was a version “of what that system had been doing in Vietnam on an infinitely larger scale continuously, for a third of a century.”

“I thought: I’m not going to be part of it anymore.”

The day the Army dropped the charges, Mr. Ellsberg said, he made his first phone call for help in photocopying what became known as the Pentagon Papers, the Defense Department’s top-secret 7,000-page history of the war — a chronicle of official deceptions — that he had in his safe at the RAND Corporation.

Robert Rheault Jr. said his father remained stoical for the rest of his life about the sudden end of his military career.

“He never spoke ill of the military,” he said, “only of certain individuals in the military.”

Robert Bradley Rheault was born in Boston on Oct. 31, 1925, the second of three sons of Rosamund Bradley and Charles Rheault, a banker and financial counselor.

After leaving the Army, Colonel Rheault spent most of the rest of his life as director of an Outward Bound program in Maine, Robert Jr. said. He also founded an Outward Bound program to help veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. He died in Owl’s Head, Me.

Besides his son Robert, he is survived by his wife, Susan St. John-Rheault, and four other children: Susanne Rheault, Meesh Michèle Rheault Miller, Nicholas St. John-Rheault and Alexis St. John-Rheault.

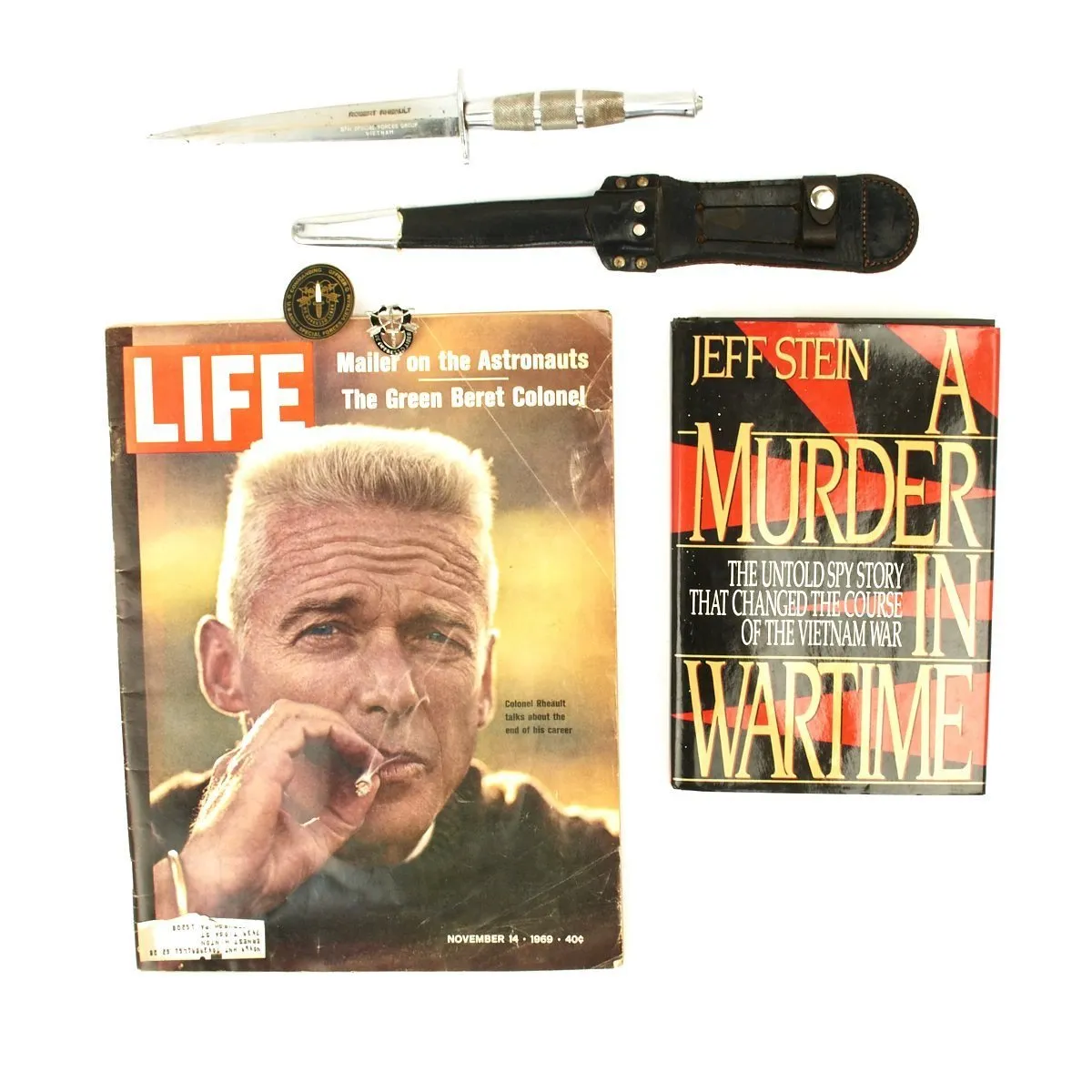

Included in this incredible set are the following pieces:

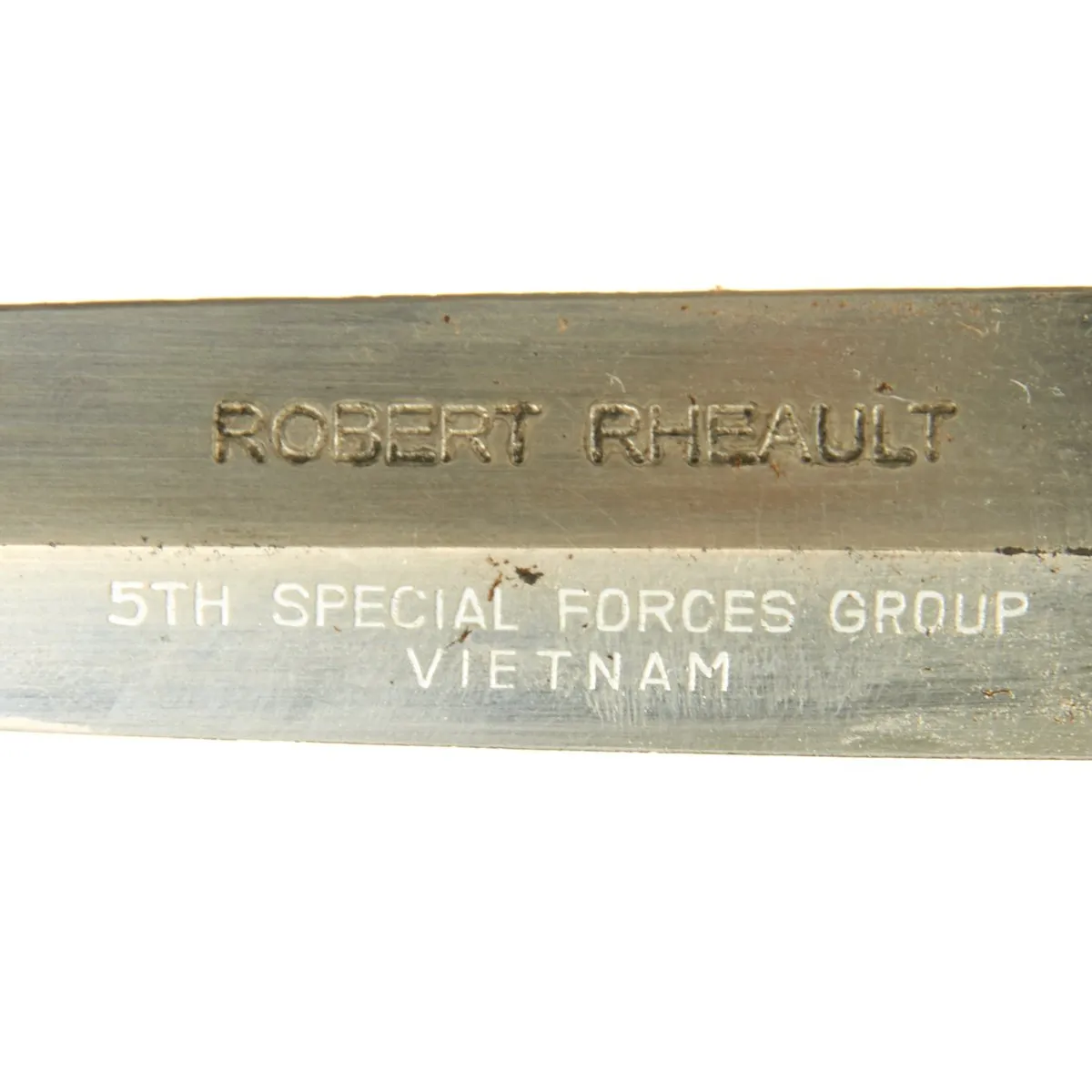

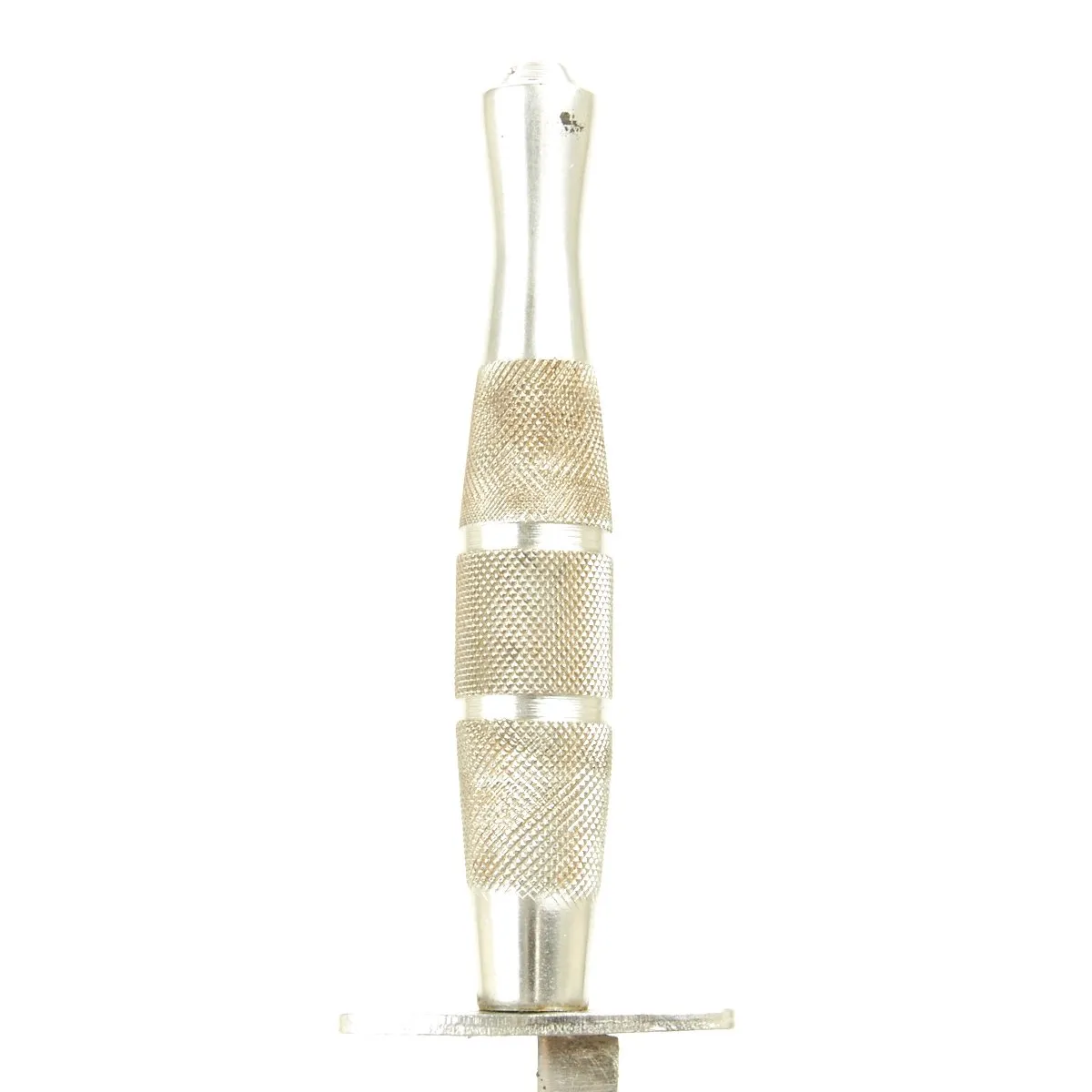

- Original U.S. Special Forces Presentation Fairbairn–Sykes fighting knife that is engraved on the blade: